LOS ANGELES—There’s an alarming—and long-lived—trend in schools across the country when it comes to discipline. From preschool to high school, discipline policies have done a terribly efficient job of pushing students out of the classroom and into the criminal justice system. And studies show that the students who find are finding themselves in juvenile correctional facilities, and eventually prisons, are disproportionately students of color, more specifically Black and Latino, and students with disabilities.

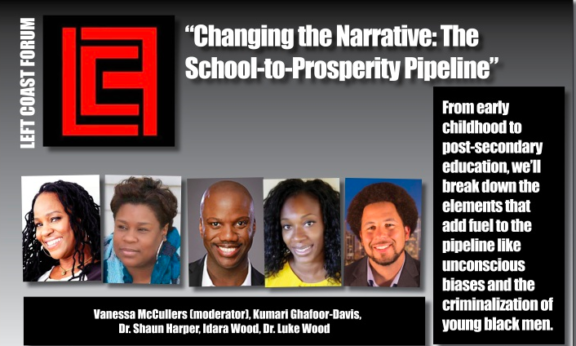

This phenomenon is called the “school-to-prison pipeline,” and since its onset, going at least as far back as the early 1990s, there’s also been a fight to combat the criminalization of students from marginalized communities. At a recent expert panel at L.A.’s Left Coast Forum, entitled “Changing the Narrative: The School-to-Prosperity Pipeline,” discussion focused on how parents can be advocates and activists for their children in a climate of racism and discrimination that denies many students’ basic right to quality education.

The panel was moderated by Vanessa McCullers, Executive Director of Moms of Black Boys United, Inc. (MOBB). She was joined by Kumari Ghafoor-Davis, founder of Optimistic Expectations; Dr. Shaun Harper, a professor at USC and Executive Director of the Race and Equity Center; San Diego State University early childhood education professor Idara Wood; and Luke Wood, also an education professor at San Diego State.

Discussion at the event centered on the way that students have to deal with implicit (unconscious) bias in school, the demographics of who is in the school teaching Black and brown students, and the ways that parents can get involved in being advocates for their children.

“Starting as early as preschool, many Black students are dealing with racial bias,” McCullers stated. Idara Wood expounded on McCullers’s assertion, arguing, “Clear racial bias and unconscious bias, also called implicit bias, plays a part in the school-to-prison pipeline.” She noted that “teachers having implicit bias influences the way they treat particular students.” Luke Wood added to the sentiment, citing the fact that “Black boys are 9.9 times more likely to be suspended than their [white] peers.”

He is one of the authors of the 2018 study Get Out, which presented research on Black male suspensions in the California school system. In the study, a variety of findings are noted. One is that while African Americans account for only 5.8 percent of California’s public school enrollment, they represent 17.8 percent of students who are suspended in the state and 14.1 percent of those who are expelled.

Luke Wood explained that California serves as just one example of a larger problem that stretches far beyond the state’s borders. “[There’s a tendency] for teachers to view Black children as having less intelligence. This is where the three D’s come in: distrust, disdain, and disregard. There’s a pervasive pattern of low expectation of Black children from childhood all the way into adulthood,” he said.

“We [as parents] have to get involved,” Ghafoor-Davis stated. “We can’t assume our kids are going to navigate this on their own. There is so much implicit bias in the education system,” she said. The panel delved into some of the factors that contribute to Black children being discriminated against. A particular one that was highlighted was the racial makeup of the school staff in comparison to the children they serve.

“There is a higher percentage of white teachers than teachers of color,” Idara Wood stated, referencing the Department of Education statistics showing that 80 percent of the nation’s nearly four million public school educators are still primarily white. This is particularly true in the public education system, which also happens to have the largest concentration of children of color. “There’s a disconnect between the two [communities]. Relationships aren’t being nurtured,” she said.

Speaking on the training of this workforce of teachers and school administrators, Dr. Harper commented, “The race of the principals of these schools [of preschool through 12th grade] is white as well. Very little happens in teacher and principal training courses that tackle implicit racial bias.

“There’s a serious policy opportunity here to change that. Is training enough? No. You need more teachers and school leadership bodies of color. There needs to be a training of the white faculty already there. This training also needs to be preemptive, before the teachers even reach the classroom, but also in their college courses,” Harper advocated. “Schools push for more bodies [of students] on the campus because it equals more money, but they don’t push for diversity in staff. We need to start addressing how to get more Black and brown teachers in the classrooms and hired,” Ghafoor-Davis added.

This focus on who is in the schools dealing with the students connects to one of the main factors attributed to the growth of the school-to-prison pipeline—increased police presence in schools. As noted by the ACLU, many underserved schools rely on police, rather than teachers and administrators, to maintain discipline. The officers sent in, often called School Resource Officers (SRO), have little or no training in working with youth.

In a 2011 report from the Justice Policy Institute, it was noted that when law enforcement is on-site, students are more likely to be arrested for infractions rather than being disciplined by school faculty. As the report argues, “this leads to more kids being funneled into the juvenile justice system, which is both expensive and associated with a host of negative impacts on youth.”

McCullers highlighted, in a video presentation, a new approach that is emerging to combat the so-called zero-tolerance policies that are another factor in the school-to-prison pipeline—restorative justice practices. Restorative justice in schools employs techniques that focus on repairing harm done to relationships through an inclusive process that engages students and faculty. Yet, although these new approaches show promise, the trajectory of the impact on the school-to-prison pipeline looks bleak for the students of color most affected by it if not confronted.

Black students make up 16 percent of the total public school enrollment nationwide, yet they comprise 33 and 32 percent of in-school suspensions and of out-of-school suspensions respectively. Excessively harsh punishments, expulsions, and suspensions have been shown to lead to worse life outcomes for students. This includes possibly not finishing high school, which, in turn, leads to a higher chance of being incarcerated in the future.

“Parent advocacy is important in this fight,” Ghafoor-Davis asserted. Addressing the role teachers unions can play in increasing diversity and combating racial bias, she added, “that falls on the leadership. Union leaders have to push for this change as well. That leadership, which can often be white, has to see this issue as important.”

“We have to help to continue to raise consciousness to this issue,” McCullers stated in closing the panel. “If we [parents] don’t do it, who will? If not now, when?” she asked. Ghafoor-Davis echoed this sentiment, urging the audience, ”Parents can be the best advocates for their children. Get involved.”

Comments