In the fall of 2017, not long after Derrianna Ford began her freshman year at Mather High School on Chicago's North Side, she was standing at her locker when an older student approached her. Unprovoked, the junior started throwing punches, she said.

The fight lasted an exhausting three minutes. Two police officers were usually stationed in that very hallway; that day, they were nowhere to be found, Derrianna said. Their absence instilled a skepticism of school police that was magnified by what she described as the arbitrary arrests of friends and other students during her sophomore year.

"They were arresting everyone, dragging them out of class," said Derrianna, now 16. "People were arrested for stealing something, for not listening to the teacher, for having a bad day."

Derrianna is among a growing chorus of activists and officials who, in the aftermath of George Floyd's killing, are expanding the call to re-examine American policing and are clamoring to defund the men and women known as school resource officers, or SROs, the law enforcement agents stationed in public schools.

Their voices may be amplified right now, but their goal is one that advocates have been advancing for years. It is part of a long effort to clamp the so-called school-to-prison pipeline, which activists say disproportionately affects minority students, with a new mindset about "how we love and value our young people today," said Maria Degillo, coordinator of a team of student activists called Voices of Youth in Chicago Education, or Voyce. "We want nurses and psychologists. That's what we're really fighting for."

In some cities they've succeeded. In Minneapolis; St. Paul, Minnesota; Denver; Sacramento, California, and elsewhere, school officials have ended contracts and relationships with local police departments since Floyd's death May 25. In Los Angeles, the board of the country's second-largest school district voted June 30 to redirect 35 percent of its police budget — or $25 million — toward supporting "Black student achievement," the district said. If enacted, the cuts could lead to layoffs for 65 of the district's 471 officers, a move that Todd Chamberlain, who resigned as chief of the Los Angeles School Police the next day, said made his job "unachievable."

"In good conscience, and in fear for safety and well-being of those I serve, I cannot support modifications to my position, the organization and most importantly, the community," he said.

And in several other cities — from Lynchburg, Virginia, to Pittsburgh — advocates are pressing districts to use money typically budgeted for police on counselors, restorative justice practices, social workers and mental health providers.

Advocates are pressing districts to use money typically budgeted for police on counselors, restorative justice practices, social workers and mental health providers.

In Chicago, where Derrianna is part of Voyce, the effort has lasted more than a decade. The push is likely to intensify in the coming weeks, as possible hearings in the City Council and a vote by the Board of Education approach.

Some city officials, including Mayor Lori Lightfoot, have argued against removing police from schools, saying that they need security and that a series of recent reforms is already underway.

"The key message here is to be responsible," Chicago Public Schools CEO Janice Jackson said during a recent news conference. "We cannot be reckless. We cannot be overly emotional in this decision, because these decisions are life or death."

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, nearly half of U.S. public schools — or 77,300 — had a school resource officer in 2017 and 2018, the last school year for which data are available. Although officers have been in schools for decades, their ranks grew considerably after 1994, when President Bill Clinton signed the Gun Free Schools Act in response to a rise in campus gun violence.

The law, which required public schools to adopt "zero tolerance" policies toward students who took guns to school, mandated an immediate one-year suspension. It was backed by federal funding allowing schools to expand on-campus law enforcement presence. The expansion surged nationally after April 20, 1999, when two seniors at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, murdered 13 students and a teacher.

But researchers who have studied school resource officers say that in the quarter-century since the act was passed, there has been little evidence that they make schools safer. A 2017 study by Kenneth Alonzo Anderson, an associate dean at the Howard University School of Education, found that millions of dollars spent on school resource officers in North Carolina didn't reduce the numbers of assaults, homicides and other crimes that schools are required to report to the state.

During the 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, which left 17 people dead and 14 others wounded, school resource officer Scot Peterson didn't even enter the school to confront the shooter — a move that led to Peterson's arrest on child neglect and other charges last year.

Anderson said it isn't clear how effective school resource officers generally are at responding to mass shootings. "Sometimes an SRO approach might be appropriate for those situations," he said. "But that can't be the only reason we have SROs."

And despite assertions from the Justice Department that the officers fill a multitude of roles in schools — they are tasked with serving as everything from standard police officers to informal counselors and emergency managers — Anderson said surveys show that they mostly act as law enforcers. "We've overestimated their contributions in other areas," he said in an interview. "There's an imbalance."

Stark differences in training also make it difficult to assess how effective school resource officers are, Anderson said. The National Association for School Resource Officers offers training in best practices like de-escalation, for instance, but the group has only 10,000 members. "We've seen situations where departments and schools put officers there who never should have been there in the first place," said the group's executive director, Mo Cannady.

Officers are stationed in 72 of Chicago's 93 public schools. In a presentation to local officials this month, the school system's security chief, Jadine Chou, said that in the past, the city's SRO program was "inconsistent" and "not transparent." Training was haphazard, she said. Police officials didn't consult with school administrators before deciding which officer went where.

"Candidly, those decisions were made, and essentially SROs were placed," she said. Nor was it always clear what the officers were supposed to do, Chou added.

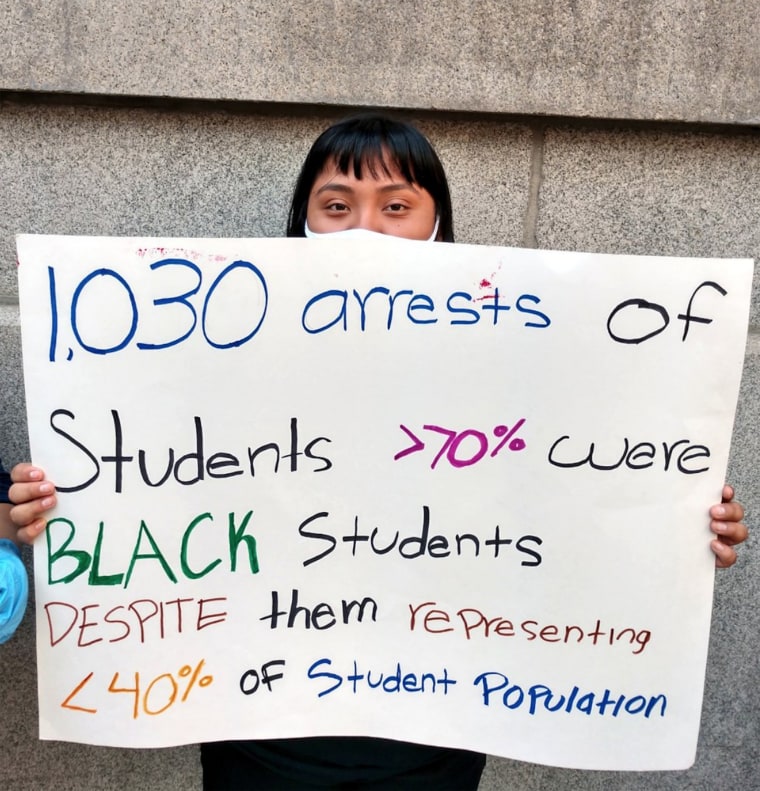

From January 2017 to this year, there were nearly 3,000 arrests in Chicago's public schools, the city's inspector general, Joseph Ferguson, said at a City Council meeting this month. Nearly 80 percent of suspects were Black, he said.

All that contact with the justice system tends to predict negative long-term outcomes, like not graduating from high school, said Marc Schindler, executive director of the Justice Policy Institute, a nonprofit research organization in Washington, D.C. Studies have shown that the most effective approach to making students feel safe is to surround them with well-trained teachers, social workers and counselors, he said.

"We need counseling, therapists and psychologists," said Derrianna Ford, the Mather High School student. "I see this with my own two eyes. People are crying in bathrooms. They don't know how to deal with stress."

The Chicago Police Department declined interview requests; in a statement, a spokesman said officers shouldn't be "the sole or even leading response to a complex web of social and economic forces." In the time since Lightfoot took office as mayor last year, the statement added, the city has "retooled its public safety strategies to ensure we are addressing the root causes of violence, including poverty, unemployment, health and lack of mental health services."

Francisco Alba, a longtime school resource officer in Denver, acknowledged that there might be racial disparities in school policing and that teachers and administrators might be too quick to call officers for routine disciplinary matters, like being disruptive, which can lead to being cited or arrested. But he said that hadn't been his experience during 15 years on the job at two school districts in the Denver area.

"My intention isn't to get them into the justice system," he said. "It's to find out what's going on with them, to talk to their parents and find out what their home life is like. I refer them to counseling. That's something we do in Denver that doesn't happen on the regular in the national scope of things."

Alba added that school districts in which police programs are abolished could end up with regular patrol officers who have far more rigid approaches to dealing with 911 calls.

"He's going to say, 'Do you have a crime? Yes or no. Do you want to pursue charges? Yes or no,'" he said.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and alerts

While the voices of activists advocating against in-school police officers have been loudest across the country in recent weeks, their ideas have been around for some time. In Chicago, Voyce and its parent organization, Communities United, began looking into the city's resource officers in the mid-2000s. The move was prompted by a high school student with a disability who had been expelled from multiple schools and repeatedly arrested.

Student activists wondered how far such arrests extended. They dug up and published data showing that in 2009, nearly 4,600 students under age 16 had been arrested in city schools. Seventy-eight percent of the arrests were for minor offenses like disorderly conduct, vandalism and fighting.

"It was shocking, but it also proved the young people who tell these stories all the time," said Degillo, Voyce's coordinator.

The students began pressing local and state officials to get police out of Illinois schools, but a compromise bill in the Legislature that would have halted their authority to arrest students failed in 2013 amid legal threats from an opposition group led by Anita Alvarez, then the state's attorney in Cook County, said Raul Botello, co-executive director of Communities United. (Alvarez didn't respond to requests for comment.)

A few years later, another effort that sought to swap police officers for mental health providers and counselors also initially gained traction with state lawmakers, Botello said. But the campaign fizzled in 2018, this time because political support vanished after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, which Botello said led lawmakers to hesitate.

"I felt at times defeated," said state Sen. Kimberly Lightford, a Democrat who worked with the group in the Statehouse. "The goal of trying to assist students and their families — I felt it was always starting over."

The latest push began days after Floyd's death. Voyce held news conferences with students like Derrianna Ford. They met with Board of Education members and urged them to redirect a $33 million contract for school resource officers toward alternatives to policing. And they worked with local elected officials on an ordinance that would do the same.

Last year, every school voted to keep them, but on July 7, Northside College Prep voted again, this time to remove the officers. The school was the first in the city to do so. A spokeswoman said Chicago Public Schools fully supported the vote and will help Northside develop a safety plan without school resource officers.

On June 22, two days before a vote by the Board of Education over the future of the contract, the school system held a news conference with Chicago Public Schools CEO Janice Jackson and several high school principals, all of whom supported keeping police in schools.

Jackson acknowledged "real concerns" over school resource officers but said reforms were already in the works: A new agreement with the police department established a method of selecting officers that includes principals, she said. Police roles and responsibilities were more clearly defined. And each school — through an elected council — is now in charge of determining whether school resource officers should stay.

A local alderman, Roderick Sawyer, also said he's aiming to get a hearing on the ordinance later this month in the City Council. Voyce activists say that in the meantime, they'll keep pushing to dismantle a system-wide alliance between police and public schools that they believe excludes students' voices.

"There is no stopping this," Derrianna said.