This

is

Solitary

By Natalie Chang

Illustrations by Simon Prades

Click icons for audio footnotes from Vaughn Brown, a former juvenile inmate at Rikers Island

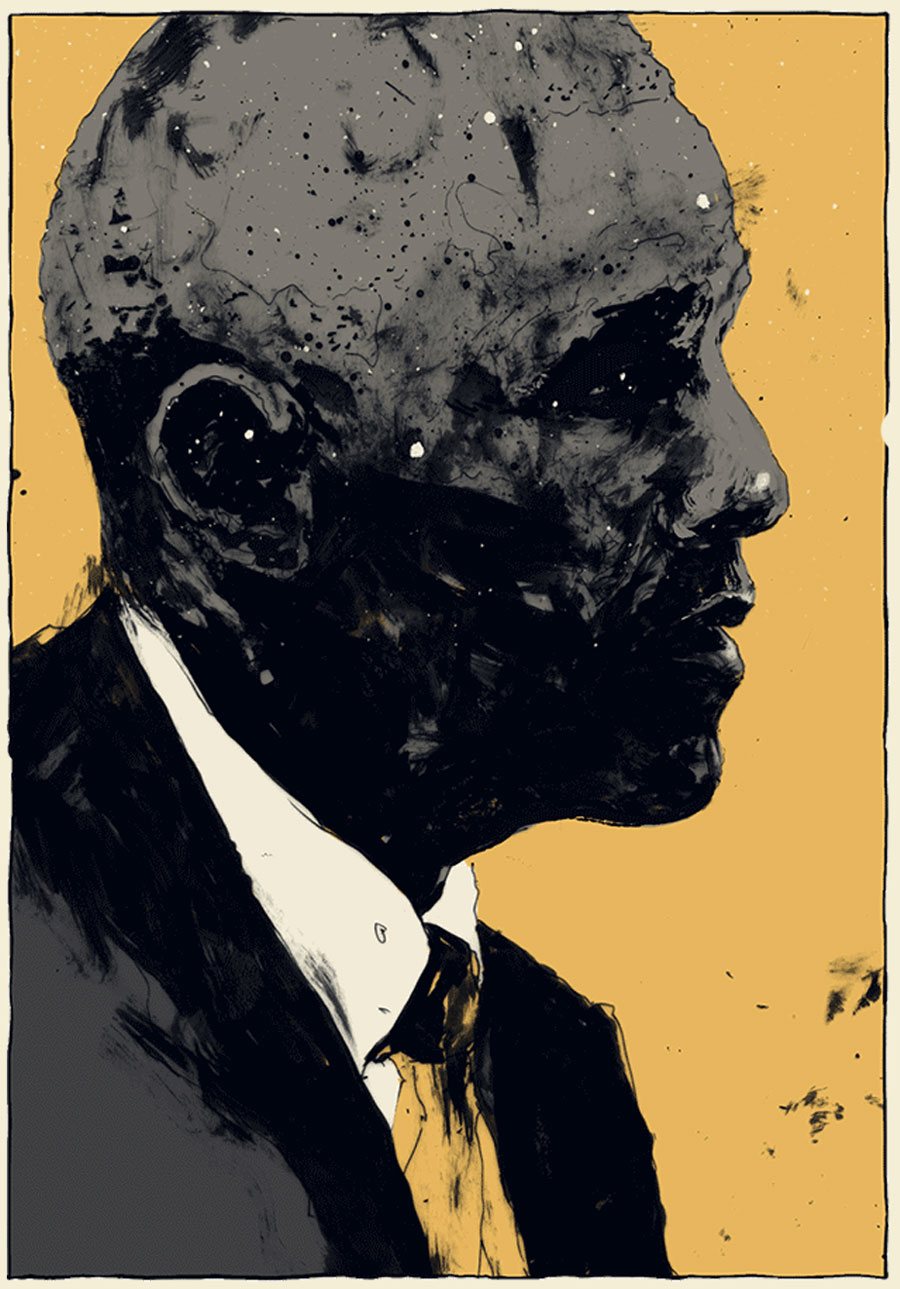

Jonathan McClard, 16, “leaned forward” toward an officer. A 17-year-old in California “made a smart remark.” Kalief Browder, 16, told another inmate to stop throwing shoes at people. Albert Woodfox, who was in solitary confinement longer than any other American, was too political for guard administrators’ tastes. Barbra Perez, a trans woman, was placed in solitary “for her own protection.” Many are accused of having gang affiliations by inmates being questioned under duress. Some are just on a prison guard’s bad side.

In other words, prison guards and administrators often throw individuals in solitary for minor, arbitrary reasons. Zoom out: Overcrowded prisons and inadequate staffing mean that inmates are placed in solitary when there is no physical room in general holding, or no staff to attend to them. Zoom out one more time: The system of mass incarceration and the sheer number of people being sent to jail and kept waiting for trials produce chaotic backlogs, and prisoners’ voices get lost.

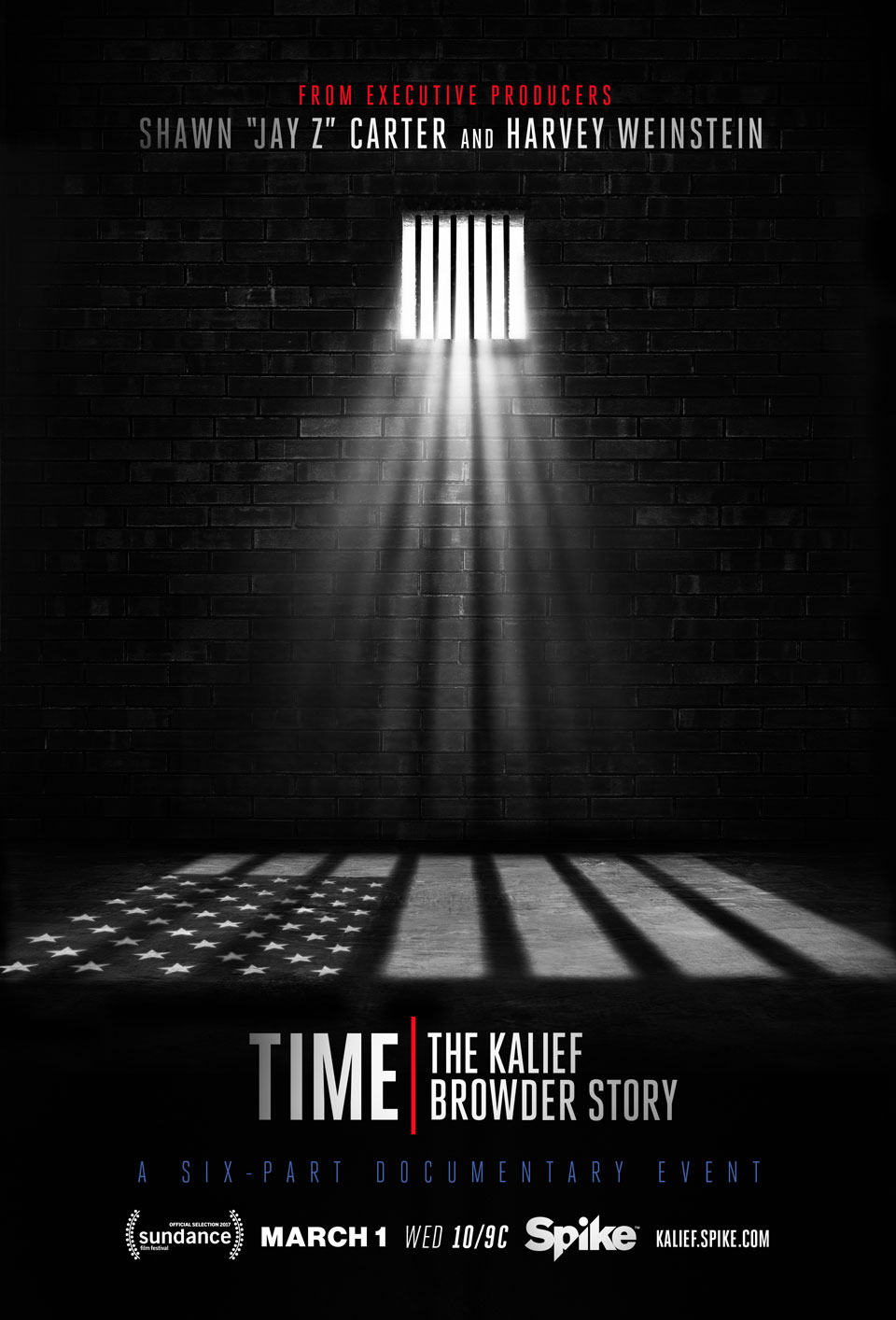

Click here to watch the trailer for time: the Kalief Browder Story | Premieres March 1

But inmates also land in solitary for their “protection,” perhaps because of their size, or age, or sexuality. “There’s a whole range of reasons that kids can end up in solitary that have nothing to do with their behavior,” says Marc Schindler, the executive director of the Justice Policy Institute, one of the leading organizations in the Stop Solitary for Kids coalition.

Data that measures the movement of inmates through our criminal justice system is spotty at best, and even less comprehensive when it comes to juvenile inmates. In 2013, the Annie E. Casey Foundation estimated that roughly 70,000 inmates 21 or younger were imprisoned in the United States, while a 2010 report by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention found that some 35 percent of surveyed juvenile inmates had been isolated during their sentence. Solitary confinement is considered a form of torture ![]() by more than one human rights organization, and it falls disproportionately, like the prison system as a whole, on black and brown prisoners. It also has not been shown to reduce violence in prisons or to improve inmate behavior. “If you talk to people in solitary confinement, very few of them are out of control,” says Dr. Terry Kupers, a psychiatrist who has studied the effects of solitary confinement for decades. “Most of them are quiet and thoughtful.

by more than one human rights organization, and it falls disproportionately, like the prison system as a whole, on black and brown prisoners. It also has not been shown to reduce violence in prisons or to improve inmate behavior. “If you talk to people in solitary confinement, very few of them are out of control,” says Dr. Terry Kupers, a psychiatrist who has studied the effects of solitary confinement for decades. “Most of them are quiet and thoughtful.

“They don’t know why they have to spend so much time in solitary.”

The psychological effects perpetrated by solitary confinement are difficult to quantify and summarize, ![]() partly because those effects run the gamut of disordered behavior. A host of studies and experts have pointed to anxiety and panic attacks, hallucinations, loss of impulse control, depression, memory loss, and the overall decline of cognitive function. In young inmates, those effects are amplified as their developing brains struggle to adapt to conditions that run counter to healthy, socialized behavior.

partly because those effects run the gamut of disordered behavior. A host of studies and experts have pointed to anxiety and panic attacks, hallucinations, loss of impulse control, depression, memory loss, and the overall decline of cognitive function. In young inmates, those effects are amplified as their developing brains struggle to adapt to conditions that run counter to healthy, socialized behavior.

Most alarming, rates of self-harm and suicide skyrocket ![]() in inmates who are held in solitary confinement. Somewhere between three and eight percent of the country’s prison population, they account for 50 percent of prison suicides. “That’s a stunning statistic that says isolation fosters or causes suicide,” says Kupers. Self-harm, he says, “is something I don’t otherwise see in grown men. Cutting becomes much more common with juveniles. In solitary confinement, it becomes an epidemic.”

in inmates who are held in solitary confinement. Somewhere between three and eight percent of the country’s prison population, they account for 50 percent of prison suicides. “That’s a stunning statistic that says isolation fosters or causes suicide,” says Kupers. Self-harm, he says, “is something I don’t otherwise see in grown men. Cutting becomes much more common with juveniles. In solitary confinement, it becomes an epidemic.”

The worst part about solitary confinement is that it doesn’t end, even when it does. ![]() As Brian Nelson, a former inmate who spent time in solitary, wrote in Hell Is a Very Small Place: “The worst part is I think I’m still there. I’m so afraid I’m gonna wake up and be back there.” Enceno Macy, who was first put in solitary when he was only 13, wrote that solitary “encouraged me to retreat deep into a demented reality where I was so alone, it made me feel as though I wasn’t meant for this world. I still feel that way to this day—like I don’t fit.”

As Brian Nelson, a former inmate who spent time in solitary, wrote in Hell Is a Very Small Place: “The worst part is I think I’m still there. I’m so afraid I’m gonna wake up and be back there.” Enceno Macy, who was first put in solitary when he was only 13, wrote that solitary “encouraged me to retreat deep into a demented reality where I was so alone, it made me feel as though I wasn’t meant for this world. I still feel that way to this day—like I don’t fit.”

Kalief Browder, after spending three years in Rikers Island, two of which were in solitary, took to locking himself in his room and pacing. He had always maintained his innocence, and finally the case was dismissed because there was no evidence of his guilt. After he returned home, his family members said he was paranoid and withdrawn, though growing up, he had been known as fun, smart, social, engaged. His mother, Venida, used to call him “Peanut.” After his time in prison, he told her more than once that he didn’t know if he could trust her. “Mentally, he was still in Rikers,” she told The Marshall Project.

“His personality was gone. His happiness was gone. You saw a darkness in him, versus the bubbly, the energetic, the outgoing from before,” says Deion Browder, Kalief’s older brother. “He became a shell.”

“We really have to help them dig themselves out of a hole that they were placed in, quite literally,” says Schindler. “We have to recognize the induced trauma.”  Some states are trying. Missouri, for example, eliminated solitary holding cells for juveniles in favor of dorm-like settings. In Indiana and Ohio, solitary for juveniles is severely restricted. “There’s no question that it can be done,” Schindler says, but states and institutions must be willing to invest the time and money required for programs that improve staff-inmate relationships and reduce solitary confinement for juveniles or, better yet, eliminate it.

Some states are trying. Missouri, for example, eliminated solitary holding cells for juveniles in favor of dorm-like settings. In Indiana and Ohio, solitary for juveniles is severely restricted. “There’s no question that it can be done,” Schindler says, but states and institutions must be willing to invest the time and money required for programs that improve staff-inmate relationships and reduce solitary confinement for juveniles or, better yet, eliminate it.

But the criminal-justice and prison system that leads to a “culture of excessive solitary confinement”![]() must also change, he says: “The first thing we should do is not put [juveniles] in solitary confinement at all.”

must also change, he says: “The first thing we should do is not put [juveniles] in solitary confinement at all.”

Close

Jenner Furst

Executive Producer

Time: The Kalief Browder Story

Atlantic Re:think

What drew you to Kalief Browder's story?

Jenner Furst

I saw this as an opportunity to take one human experience and the tragedy of everything that could go wrong for a child and dissect the key issues related to his case and his journey through several systems that all failed him. From the foster care system, to the public education system, to the probation system, the bail system, the jail system, the mental health system, the solitary confinement system, the failing court system. There is so much to learn from Kalief Browder’s life about these massive failings. It could be an awakening for America.

AR

What most surprised you as you developed the show?

JF

The really shocking revelation was that a child who's being held in pre-trial detention, has not been convicted of any crime, and is technically innocent could be tortured in an environment like Rikers Island. Specifically, in the punitive segregation unit which was renowned for abuse, neglect, and corruption. We're not always doing this to the criminals and Hannibal Lecters of the world. We are treating people who are technically innocent under the law, who have not been convicted of anything, as if they are less than human.

AR

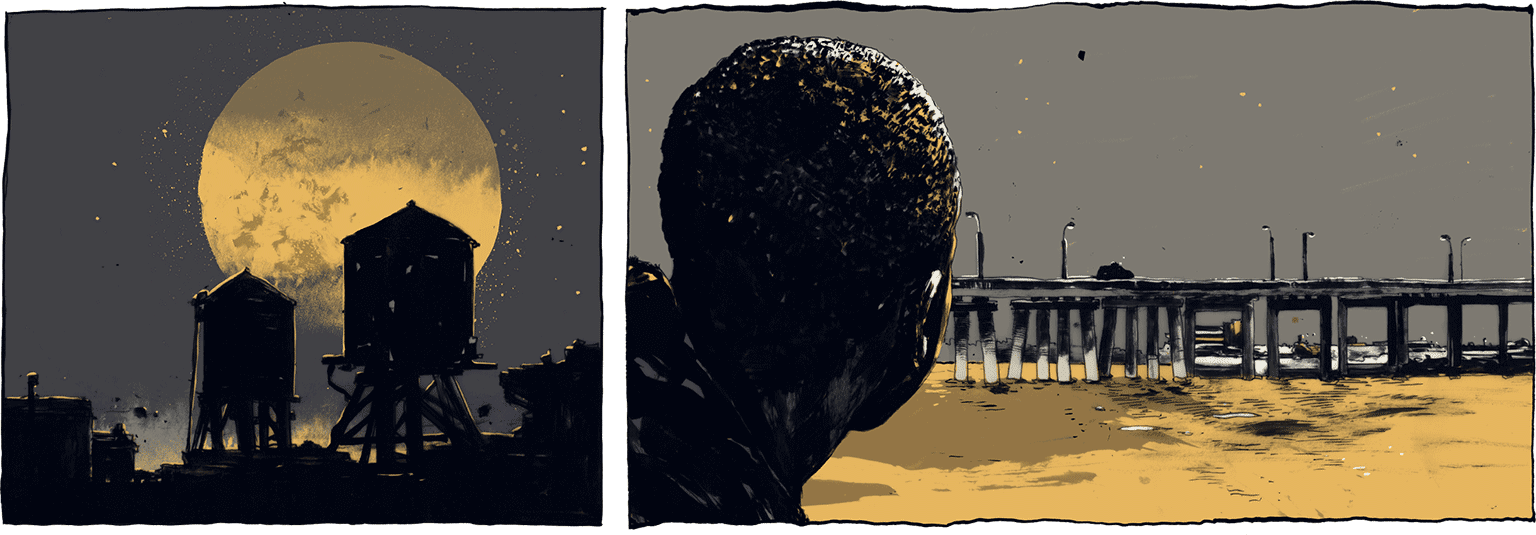

You visited Rikers’ punitive segregation building as part of your research for the show. What was it like?

JF

It's a place filled with pain and anguish, and you can feel it in the air when you walk in. You can hear it, you can smell it, and it's not just when you're inside: You can feel it emanating from the building. You can hear people yelling from outside the building. There are people who are banging on the cells in anguish, yelling profanities at you, sometimes yelling desperate calls for help, and the guards dismiss it: "Oh, they're just acting up. They're acting up because we have a visitor." Knowing what we know about brain damage, the experience of solitary, and how it is technically torture, I don't think it's just acting up. You're witnessing pain, confusion, psychosis, suicidal thoughts.

AR

What did you learn about what happens to inmates held in solitary for extended periods of time?

JF

One of our sources was able to outline how past trauma is magnified tremendously in an environment like solitary confinement. It's torture on top of torture. Someone who may have had their case dismissed after five years of crawling through the Bronx criminal court is coming home with PTSD, clinically. Some of them are coming home with permanent brain damage.

AR

And Kalief’s case really encapsulated all the injustices of the system at once.

JF

The Department of Justice had done a scathing report on Rikers, and they liken the environment to Lord of the Flies. People being beaten, multiple head shots, falsification of documents, starvation, and rat poison had been put in the food of some inmates.

And after all that, when Kalief gets out, he has no mental health services that are useful: He's floating about and he's over-medicated. It doesn't do much to break down this massive level of trauma that this young man had endured. The mental health system in New York City was one of the last systems that failed him before he died.

The experience of being in the evening news, and being in articles: It dies down. When that attention died down, the Browder family was terribly vulnerable. They felt like, “Wait a second, no one's talking about Kalief anymore. No one's here for us. Our case hasn't moved forward and we're not getting justice.” I was present for Venida Browder's passing and in the room with her when she died. I saw the collateral damage of the criminal justice system. We were with her family, knowing that they were experiencing their second murder, that her death of a broken heart was not a health issue, but a betrayal by the city of New York and by America.

This is what the work is about. We hope that people are inspired to just click through to find out what this means for them locally. This is what I hope they'll absorb from this series: the incredible human consequence of our justice system and how terribly broken it is.

Close

Close