Among the workshops listed on the website of Jessie H O’Neill, a psychologist and granddaughter of a one-time General Motors president, is Money Dearest: Healing from Affluenza.

After the publication of her 1997 book The Golden Ghetto: The Psychology of Affluence, O’Neill founded The Affluenza Project, which includes her private practice to treat money-borne maladies. The goal, she writes, is to unpack the psychodynamics that trouble wealthy families and individuals, which are typically rooted in dysfunctional relationships with wealth (or the pursuit of it).

The word affluenza, which has been used in various contexts over the last century, is a portmanteau of “affluent” and “influenza”. And because of Ethan Couch, the notorious “affluenza teen” caught on the run with his mother in Mexico last week, it appears to be fast en route from relative obscurity to household word.

But what exactly are we talking about here? Is this really a virus, even in the metaphorical sense? An epidemic? A reflection of failed parenting? And, most urgently, is it contagious?

Multiple interpretations of affluenza abound: one Christian group implores those infected with “credit card mania”, “greed fever” and “morbid despair” to “declare your independence from stuff!” Merriam Webster defines the word, in part, as “the unhealthy and unwelcome psychological and social effects of affluence regarded especially as a widespread societal problem”. (Next to affluenza, the online version of the dictionary also lists the word “affluxion”, which could suggest a combination of “affluence” and “affliction”, or some horrible version of acid reflux.)

The Couch case has touched off extreme outrage over the past few days, with scathing commentary all over the news and on social media, coming at a highly volatile time for the nation on issues of race, justice, wealth and poverty.

“We are at this time cutting food stamps to millions of kids, who will suffer from this in their lives, at the same time that we are continuing to give new tax breaks to millionaires and billionaires,” John de Graaf, co-producer of a 1997 PBS program about the phenomenon, said in an interview. “That’s affluenza in a nutshell.”

De Graaf was also a co-author of Affluenza: How Overconsumption Is Killing Us – and How to Fight Back, first published in 2001 and updated for a third edition in 2014. That book defines the term as “a painful, contagious, socially transmitted condition of overload, debt, anxiety, and waste resulting from the dogged pursuit of more”.

As de Graaf sees it, the modern age of affluenza began in the US with the 1980 election of Ronald Reagan, and the ensuing tax cuts for the rich and the erosion of America’s safety net for the poor that followed. If the billionaire real-estate mogul Donald Trump were to be elected president, he said, “then America would become the empire of affluenza”. On the other hand, the leftwing populist candidate Bernie Sanders is “the affluenza vaccine”, he said.

British psychologist Oliver James, in his 2007 book Affluenza: How to be Successful and Stay Sane, argues that the entire world is experiencing an epidemic of affluenza (he defines it as a burning envy and obsessive desire to keep up with the Joneses that can lead to severe depression and anxiety). These Joneses are not simply American dreamers of the shrinking middle class; they are more like the Couches and other families in the top tiers of wealth.

The word affluenza has been mentioned as far back as the 1800s, according to an analysis by Google Books, tracing mentions of the word over time. Its coinage has most widely been attributed to Fred Whitman, a descendant of a prominent and wealthy San Francisco family, who purportedly came up with the idea for the combination of words in 1954 as he was “looking into the problems of inherited money”, according to The Chicago Tribune.

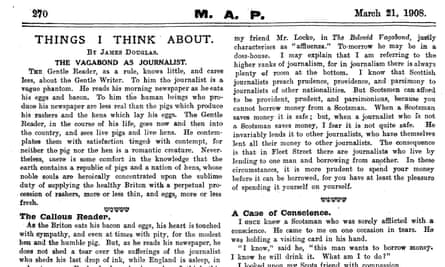

But affluenza was referenced even earlier, in 1908, by a columnist writing for a London newspaper. In the article, the columnists credits William John Locke, author of The Beloved Vagabond, a novel about an architect in 19th century France who decides to disguise himself as a tramp, with coining the term in the 1906 book. Garson O’Toole, who runs a website called The Quote Investigator , dug up the reference.

Not long after that there is a peak on the Google Books analysis (but no readily available article or book citations) at around 1920. For the term to emerge during that time period would make sense, de Graaf said, given the free-wheeling spending of the Gilded Age that came in the wake of the worldwide influenza epidemic that killed 50 million people in 1918.

This chronology brings us back to our latest affluenza case.

Ethan Couch’s 2013 sentence for killing four people and injuring nine others while driving drunk was 10 years probation and attendance at a rehabilitation facility.

This begs the question: if poverty and neglect can be used as mitigating factors in sentencing, as they often are, why can’t wealth and neglect? In fact, a deeply reported cover story in D Magazine last May documented fairly extensive neglect by Ethan Couch’s parents starting from a young age.

“It struck me that this is how the juvenile court is supposed to work,” said Marc Schindler, executive director of the Justice Policy Institute, an advocacy group in Washington, said in an interview. “It’s supposed to be individualized, tailored to the person’s needs.”

But key, Schindler added, is that families like the Couches have the resources to secure the best possible legal representation. Quoting a colleague in the criminal justice field, he said: “It’s worse to be innocent and poor in this country than to be wealthy and guilty.”

And while the story of Ethan Couch’s life thus far seems to him a clear example of highly damaging parental neglect, Schindler said that the son “is not completely blameless. There should be accountability.”

That sentiment was reflected in a column in the Harvard Crimson headlined The Many Strains of Affluenza, published after the 2013 sentencing of Couch and written by a member of the Harvard class of 2014.

The column, expressing fury over the “affluenza defense” used in the case, concluded: “Let’s remain humble, remain rooted to the world beyond the Yard – where we are swaddled in wealth. We need to remember the end result of a life of ignoring the consequences of our self-absorption is deadly.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion